28/01/2017, by Didace Gasana

Irene Sokolow works at Swedish Migration Board. On 21 September 2016, she confirmed to Swedish’ news outlet sydsvenskan that Gambia’s former interior minister Ousman Sonko, has sought asylum in Sweden, after having been fired by the then President Yahya Jammeh and fearful of his life.

But for some days now, Sonko and his former tormentor (according to him), share the same fate after a combination of Machiavellianism on the part of the opposition, Jammeh’s liability and external support, all worked in unison to seal Jammeh’s political fate. At this point, Jammeh’s political demise is common knowledge. What is not, but what actually should be, is the legality of ECOWAS’ intervention.

An OB and an international law expert, Fred Nkusi, writing in Rwanda’s daily The New Times on January 23, 2017, posed a question cum title of his piece: “Did ECOWAS have legal basis to remove President Jammeh from power militarily?” From the beginning, I imagined the author wanted to shed light on complex legal issues involved in foreign interventions. After reading the piece (http://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/article/2017-01-23/207340/), I felt betrayed.

Betrayed because my learned friend’s piece manifests acute legal poverty or was heavily edited by someone alien to international law. So wrote the author: “Under Chapter VIII, specifically in Article 52, paragraph 1, the UN Charter precludes the existence of regional arrangements or agencies for dealing with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security as are appropriate for regional action, provided that such arrangements or agencies and their activities are consistent with the purposes and principles of the United Nations.”

As a matter of fact, art 52 (1) of the UN charter precisely says the opposite. It says “Nothing in the present Charter precludes the existence of regional arrangements or agencies for dealing with such matters relating to the maintenance of international peace and security as are appropriate for regional action, provided that such arrangements or agencies and their activities are consistent with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations.”

At the risk of going extra petita, the nearest his argument would come close to international law and the UN charter is article 53 (1). Even this, the mere fact that there was no UNSC resolution under chapter VII doesn’t deprive ECOWAS’ action of its legality as explained below.

His thesis from there becomes misguided. While I agree with him that ECOWAS needed UNSC resolution acting under chapter 7, the author forgets that article 20 of articles on responsibility of states for internationally wrongful acts (ARSIWA) is very explicit that where there is consent, there is no international wrongful act. Article 20 of ARSIWA reads: “Valid consent by a State to the commission of a given act by another State precludes the wrongfulness of that act in relation to the former State to the extent that the act remains within the limits of that consent.” In Gambia’s case, it was not a matter of UNSC acting under chapter 7, it was a consent of the Gambian state. Why?

Pursuant to the Vienna Declaration on Diplomatic Relations, Barrow was duly and legally inaugurated as a head of Gambian state by virtue of being sworn in in a Gambian embassy abroad. That Barrow asked for ECOWAS help suffices to immediately trigger “volenti non fit injuria” (article 20 ARSIWA). It thus follows that ECOWAS’ intervention was nowhere close to an international wrong under international law.

However, this is not the major import of this delivery- the lesson for African opposition movements, particularly Rwanda’s, is.

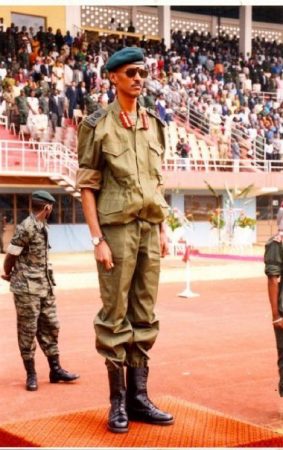

Sometime last year, I opined on these pages that African autocrats have no choice but to cling onto power even at the cost of their dear lives. Specifically, I argued as a guest on an opposition wire radio that for president Kagame to leave power, the opposition should be seen to make concessions and guarantee him a safe exit. Why? President Kagame stands accused of so many crimes that the very opposition has “volunteered” info to the ICC for his eventual indictment. Secondly, President Kagame has a civil suit in the US, whose worth is more than the net worth of more than half of Rwanda’s population. My argument was (and is) that as long as the opposition movement press him to the wall, he is left with no choice but to cling onto the thing. And, without doubt, President Kagame is a microcosm of a whole bunch of African coconut heads masquerading as crocodile liberators.

How does Gambia fit in here? Well, as soon as Jammeh conceded, the opposition turned upside down the chance of peaceful transfer of power by threatening to hold him accountable for his crimes as well as reverse all his prior international engagements. This may be politically right but it was technically wrong. Consequently, he changed his mind and decided to cling onto the fountain of immunity. It took regional bodies to negotiate his immunity and opposition take-over.

In other words, African opposition movements need to enter the psyche of the autocrat they are fighting. Leaving them with no option but suicide, death, prison or ICC, they inadvertently destroy any hope of a democratic transition. Secondly, while the global centers of power- western capitals- are certainly useful, equally useful are regional groupings without which Gambian episode would never have seen light.

This doesn’t certainly mean condoning past leaders’ excesses. Far from that, it is a technical aptness rather than political correctness that should matter in the African context.